CROATIAN FISHERMEN’S CONTRIBUTION TO WORLD FISHING

The commencement of modern fishing

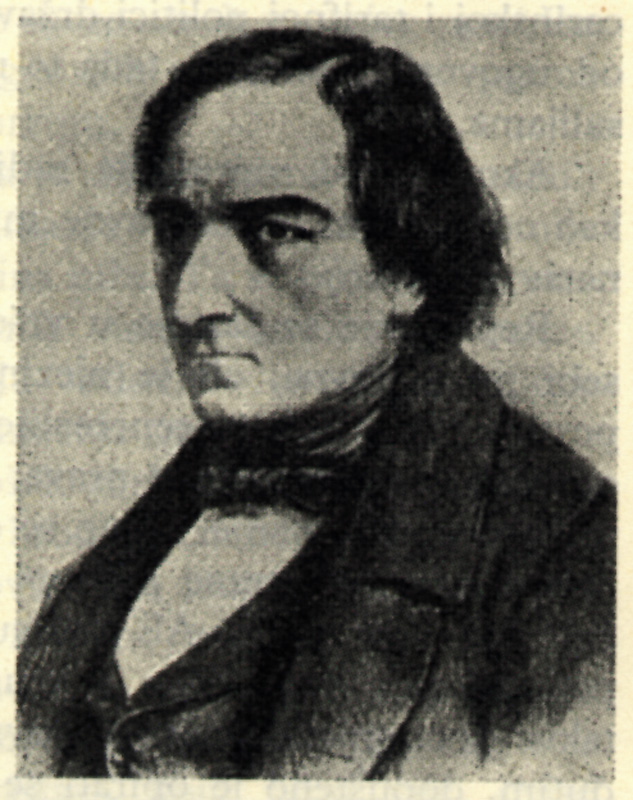

Josip Ressel – The inventor of the propeller

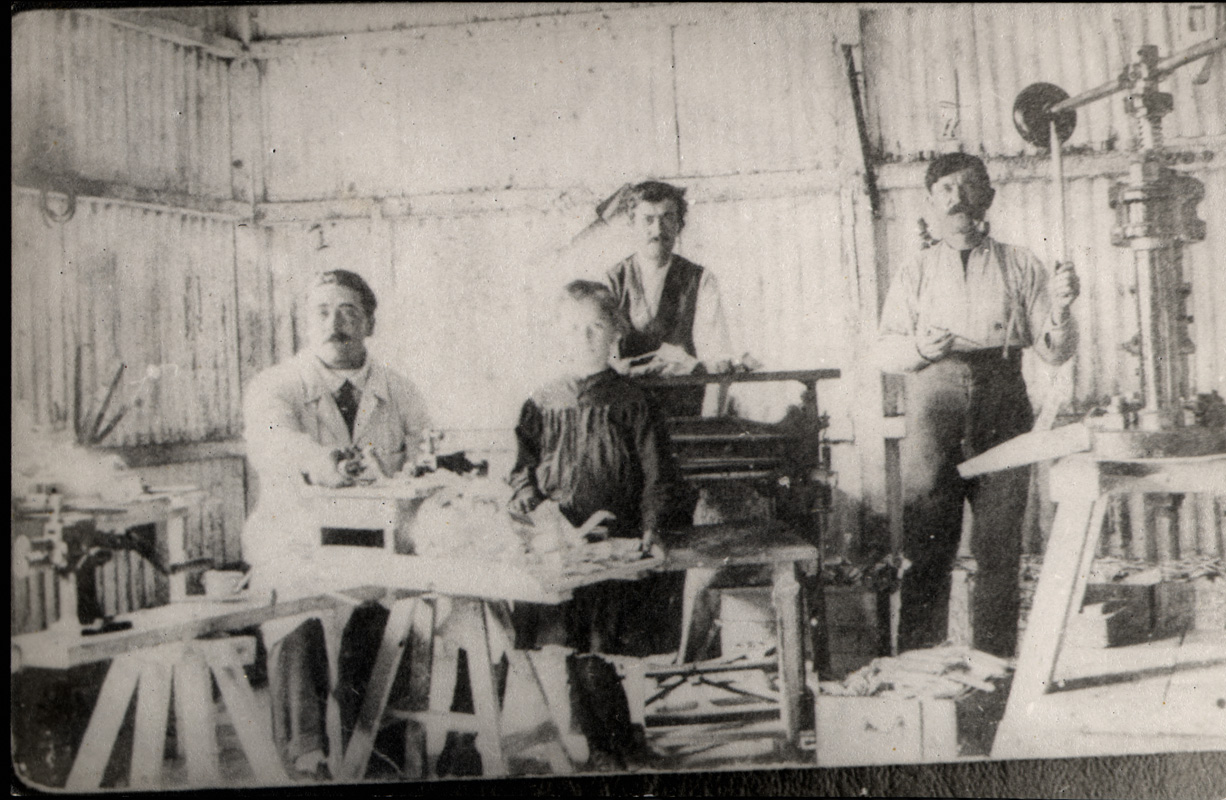

Many important inventions on modern fishing boats for deep sea fishing were invented by Croatians. It is an unbelievable fact that all those people who revolutionized world fishing with their inventions were mainly uneducated people, simple fishermen, without the technical knowledge gained within an educational system. Their lifelong experience on the sea and the hardships of the fishing trade caused them to change the current situation, to change their fishing tools in this difficult and life threatening trade.

The only exception in this line of inventors whose accomplishments changed the navigational and fishing practices of the world was the forester from Motovun (Istria) Josip Ressel, who graduated forestry in Vienna. Josip Ressel patented the boat propeller in Trieste in 1827. His invention was tested on the steamboat Civetta in Trieste’s harbour in 1829. On this occasion, after a half mile journey, a pipe in the steamboat burst and the experiment was banned by the police. Josip Ressel continued experimenting the propeller in Šibenik and thereby promoted his invention which later took a significant place in world navigational history.

Ivan Skomerža, pioneer of modern fishing on the mediterranean

The invention of the marine engine began a new period in the history of fishing. The dream of a force which could drive a boat independent of human muscles or winds is as old as the boat itself. That dream came true on the Adriatic sea in 1908.

Ivan Skomerža from Crikvenica introduced this innovation. Skomerža’s boat Dinko Vitezić with a 70HP engine was the first motorized fishing boat trawler on the Mediterranean. Up till then the trawl net was dragged by two boats powered by wind and sails. Later on, Skomerža put engines on the boats Ribar and Neptun.

Šoljan writes that his initiative was heard of in Italy, so, towards the end of 1911, a group of experts arrived to check out the innovation and Ivan Skomerža’s experience with this new way of fishing. From Italy to Crikvenica came the principal of The Venetian Fishing School from Chioggia, the principal of the nautical school Scilla from Venice, and shipbuilding engineer Brodolli from Genoa.

During the following years, Skomerža acquired a whole fishing fleet of motorized trawlers and established the fishing society Nekton in Rijeka. That was also the first shareholding fishing society on the Adriatic. In 1912 Skomerža’s supply boat Valerija, which provided his boats with fuel, food, fishing tools, mechanical workshop and medical services, joined his fleet. That supply boat of Skomerža’s was the first of its kind in the Mediterranean.

Skomerža’s fishing fleet was accompanied by the transport boat Kondor with autonomous freezers and refrigerators and pools for live fish. This was also the first of its kind on the Mediterranean. Besides that, his boat Kondor, as Šoljan writes, was the first boat on the Mediterranean to use widening boards to drag the trawl net following the example of the Nordic trawler.

In 1909 he was the first on the Adriatic to successfully use the purse seine, which even captain Šime Vuletić from Vela Luka and fishing supervisor Petar Lorini from Sali on Dugi Otok had both failed to do.

In the same year of 1909, Skomerža was the first in the Mediterranean to use a petroleum lamp for fishing pelagic fish at night. This was at the time when the acetylene lamp was still new on the Adriatic fishing scene.

In order to measure Ivan Skomerža’s contribution to the history of Adriatic fishing in the twentieth century, we must bear in mind that, in all of his modern solutions, he was far ahead of the Italian fishermen who had expert and government support. His motor fishing boat appeared a good ten years before the first experiment was trialed with marine engines on the fishing boat in Pescara in 1918. At the time when Skomerža had a fleet of twenty trawlers which fished using the Norwegian type of trawler with widening boards, the Italian trawlers were still fishing with nets drawn by wind power.

The rise of Ivan Skomerža, who dreamed of building a complete fleet of about sixty engine powered fishing boats, was halted by the First World War. His fishing society Nekton closed down. There only remained the memory of a man who, at a dynamic time of world change, was the most active participant in the fishing industry, not only on the Adriatic, but on the whole Mediterranean.

Fishing expedition – Lampedusa

The bad fishing years on the Adriatic in the second half of the nineteenth century were the reason why Dalmatian fishermen left their shores far behind. Carlo Marchesetti wrote in 1882 that Croatian fishermen from the island of Hvar, with thirty two boats in the waters of the small Italian island Lampedusa near Tunisia, were catching between twelve to fourteen thousand barrels of sardines per fishing season. Marchesetti wrote that these fishermen fished in nearby African waters, and sold the salted fish in the Levant and in Italy.[3]

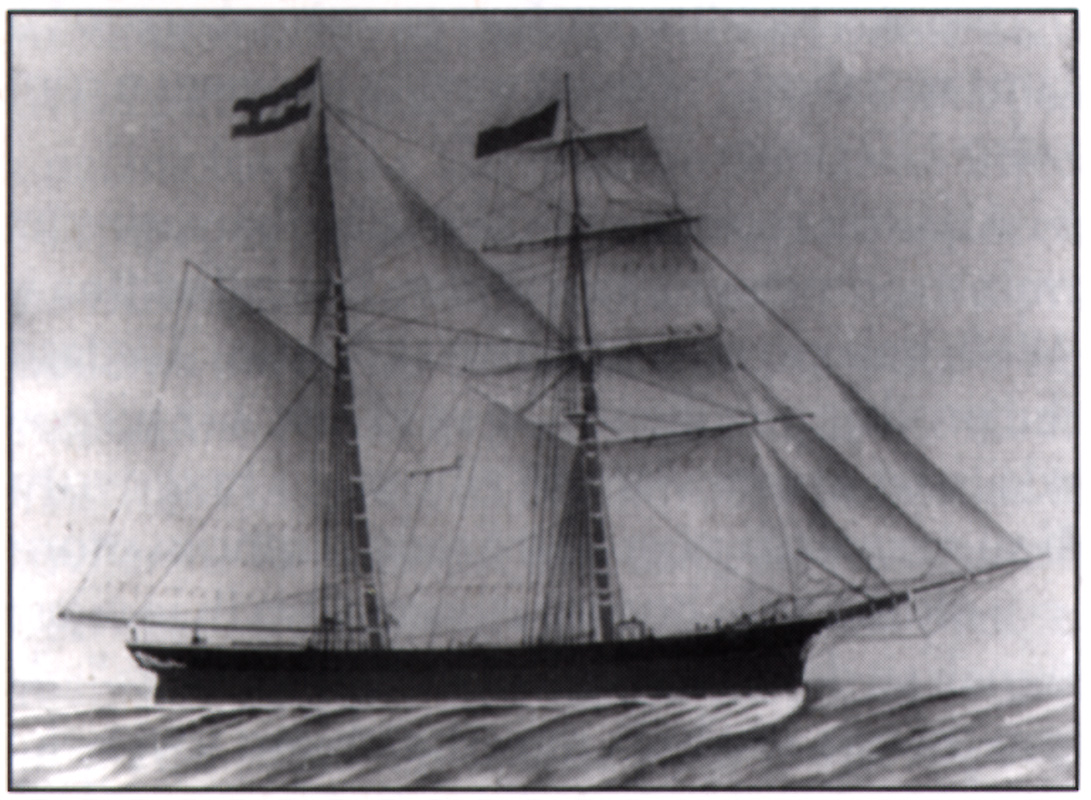

Renowned Croatian ichthyologist and fishing historian Šime Županović, describing those Dalmatian fishermen’s undertaking in the Mediterranean, speaks of Hvar’s Tomas Novak’s discovery of a rich fishing area around the small island of Lampedusa. Šime Županović writes that, in the harbour of Patras, captain Tomaso Novak saw a boat loaded with salted sardines and learned from the crew that the fish was caught around the small island of Lampedusa. He then organized an expedition with the sailing vessel Moise. Other fishermen from Stari Grad and Jelsa on Hvar, from Trpanj, from Vela Luka and Komiza, also later took part in this undertaking. Captain Šime Vučetić from Vela Luka, together with his sons, as Šime Županović writes, organized a fishing expedition with the schooner Mileva into Tunisian and Algerian waters. Captains Vicko and Jakov Novak from Hvar left the Mediterranean and went to the Atlantic coast to establish a fish cannery in Lagos in southern Portugal which is, even to this day, still in operation and in the ownership of the Novak family.

Fishermen from Komiza at the “end of the world”

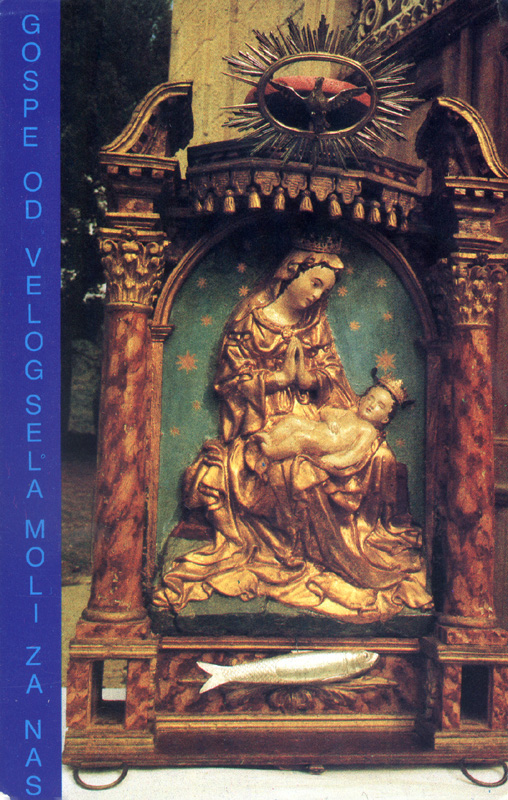

Dalmatia is the cradle of the fishing industry on the Adriatic. In 1870, in Komiza on the island of Vis, the first fish cannery was established for processing fish in the Nantes tradition (ad uso Nantes), meaning the fish was fried in olive oil and canned. The expansion of this oldest industrial production in Dalmatia resulted in the opening of seven factories in Komiza and factory owners from Komiza opened a chain of fish canneries throughout Dalmatia. In order to constantly supply all those factories with fish even during the bad fishing years, they sent their entrepreneurs to Portugal and Spain to organize fishing and the salting of fish there.

At the end of the nineteenth century, the Mardešić factory from Komiza erected wooden buildings for salting sardines in Spain on the cape of Finisterre. In this way, the people from Komiza advanced towards the bountiful seas beyond the Adriatic right up to the end of the known world, to Fisterra, as it was called in the Galician language (from the Latin finis terrae – end of world). At that fatal point – Cabo Fisterra, on that most dangerous European cape and westernmost point of Europe, as the old seafarers thought, the factory owners from Komiza erected salteries to salt sardines and anchovies. At that point, at the end of the nineteenth century, the first barrels of fish were salted on the Atlantic coast of Spain. At that same point twenty boats from the famous Spanish Armada had sunk to the bottom of the sea in 1556, on the coast whose name Costa da Morte commands fear and respect. The sea rock Centolo evokes the dread of seafarers who, while sailing in the fog, hear the wail of Vaca de Fisterra – the cow of Fisterra, as seamen call it – which is the siren from the lighthouse which warns of danger.

Today La Coruna, the Galician town near Finisterra, is the largest fishing port in Europe. It began with the afore-mentioned wooden salteries, established by the people from Komiza on that Coast of Death at the end of the known world. It began below the lighthouse from which Vaca de Fisterra wails in the thick ocean fog towards the endless Dark sea (Mare Tenebrosum), as it was called by the Roman conquerors of Galicia.

From 1903 up to the First World War, the person in charge of the salteries established on the Coast of Death, was Dinko Bozanic Pepe, a fisherman from Komiza. When he returned to Komiza from his Galician expedition, he told the stories which remained in the oral tradition of his family and the old Komizians. The stories were about unbelievable catches of sardines and anchovies and how the Galician fishermen hauled their nets full of fish with the help of oxen onto the sandy shores and about how, not knowing what to do with the leftover fish, they used it to fertilize fruit trees. He told of beginnings of the fishing industry in Spain whose pioneers were the Dalmatian fishermen. He spoke of the storms and of the end of the world where the Dark Sea with its terrible monsters began. He told of the Coast of Death – Costa da Morte – which sent boats and sailors to their death.

That enterprising spirit of the Dalmatian fishermen and factory owners spans pages of a unique fishing saga. Although completely unresearched and almost unknown in Croatian fishing history, it was actually the beginning of the world promotion of Croatian fishermen.

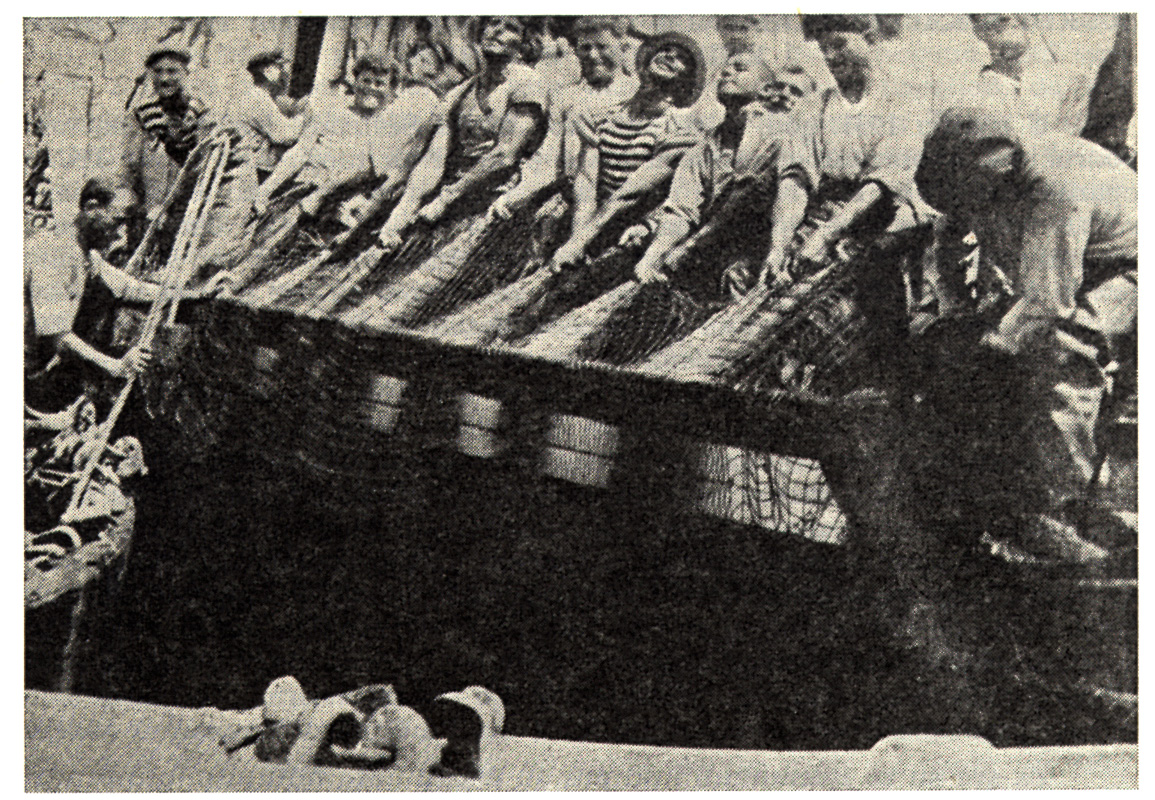

Jakov Kuljiš Amerikana: fisherman from Komiza and honorary american citizen

For centuries on the prow of svjećarica (sea fishing boat using artificial light to catch fish at night) there has shone a light to catch pelagic fish. In the former times, the oarsman of this boat had to cut an enormous amount of pinewood by day to keep the fire burning all night on the prow. On the svićalo (iron grid positioned so that it stood out above the sea on the left-hand side of the prow) a fire of pinewood was lit. The light of this fire would draw schools of sardines, anchovies and mackerel. When the fish gathered in the dark night, attracted by the firelight, another fishing boat, with its own net, would envelop the fish and svjećarica. And then, the fishermen from the shore would haul the net towards shallow waters. People have fished in this way since ancient times.

The term šijavac means the oarsman in svjećarica (lightboat) and that word originates from the verb šijavat which means ‘to row backwards’. In those times while the fire was burning on the prow, the oarsman had to maintain his boat’s position all night, rowing against the wind and back water so that the wind which blew from the stern carried the smoke and flames away from the boat, over the prow. Had he rowed towards the wind, the flames and smoke would have entered the boat and it would have been impossible to survive in it. And so that oarsman, by day, cut pinewood and, by night, rowed till dawn regardless of whether there was fish or not below his fire because There’s always hope as the light over the prow! – as the old Komizian saying goes. And so it went on for centuries. Today this would be an unbelievably laborious task. And the problem was, that due to the constant cutting of pine trees, the forests could not be renewed and consequently, many of our islands were left bare. People from Komiza were even forced to go to Italy to buy pinewood on the peninsula of Gargano. With their traditional cargo boats (bracera) and their peculiar fishing boats (falkusa), they brought to Komiza pine wood for the night fires for fishing and also for boat building as the hills of Komiza were barren from constant woodcutting which had lasted for centuries.

Ivan Dellaitti’s acetylene lamp

Lime carbide was discovered in America in 1891. In contact with water, it produces acetylene gas which burns and gives off a shining light. This discovery enabled numerous uses of carbide in lighting.

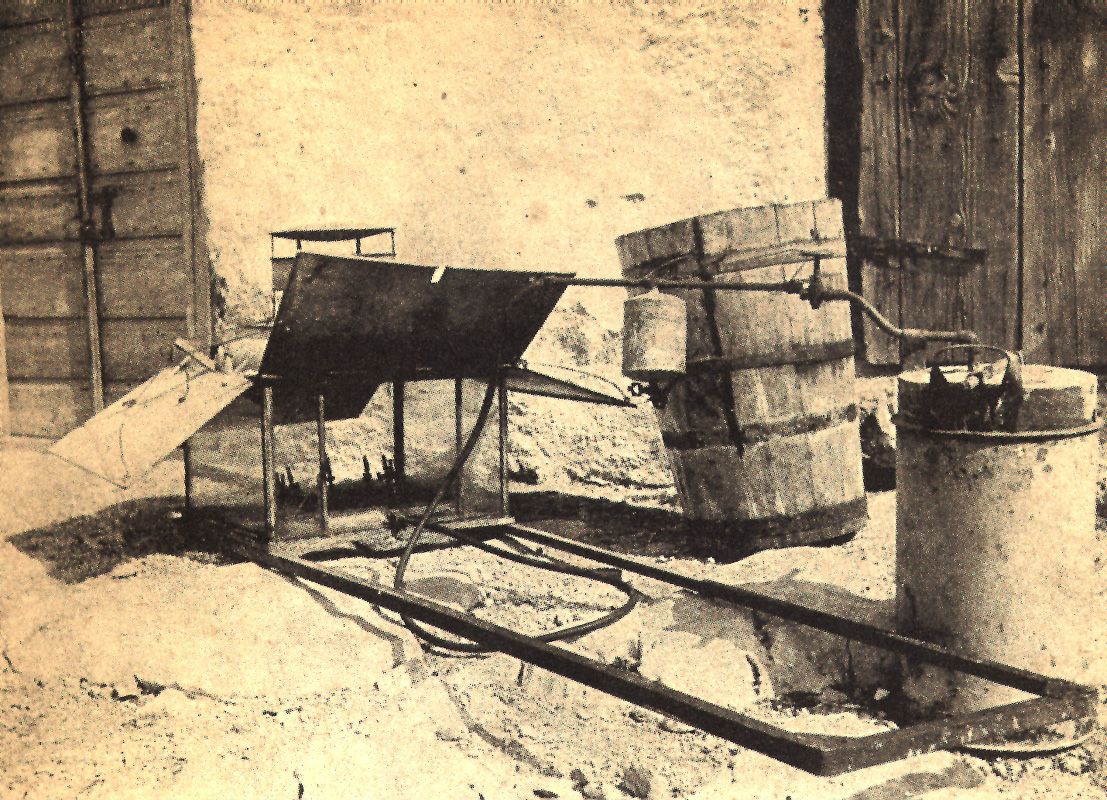

In 1898, as Petar Lorini writes, Ivan Dellaitti from Senjska Rijeka invented a device for the production of acetylene gas from carbide and constructed the first fishing lamp. Now he had to test his invention and convince fishermen that his lamp was better and more efficient than the traditional light of pinewood fire.

Petar Lorini helped Ivan Dellaitti by participating in experimentation. He approached the Maritime Office in Trieste for help and the Office demanded that he should test his invention practically. Petar Lorini then organized an experiment in Sali on Dugi Otok. On this occasion he writes: ‘We will never forget what we experienced at the moment we lit the first lamp in our own home town, that is, when the first ray of acetylene light fell from our hands onto our beautiful sea! Our hearts filled with pride, our eyes shone as we watched the crystal clear sea lit up by our new lamp and from the depths of our soul we cried heartfelt thanks: Glory to God! The day of the poor fisherman has finally arrived. Our fishing livelihood has been saved.’

TAKING THE FISHING LAMP TO AMERICA

At the same time, Jakov Kuljiš Amerikana, a fisherman from Komiza, also started experimenting with the acetylene lamp. In his house of birth in Komiza, one can still find the prototype of the acetylene lamp that he constructed before leaving for America. At that time, Komiza’s sources of pinewood had been depleted. Photographs of old Komiza at the end of the nineteenth century show completely bare hills in the background and Kuljiš’s experiment was greeted with great interest. His invention spread quickly and proved to be very successful.

But, the inventor of this lamp dreamt of the rich seas described in the letters of emigrants from Komiza. Caught up in the wave of migration, he abandoned his oars and difficult fishing life on the off shore islands of the Vis archipelago and set off for America carrying his acetylene lamp with him.

At the beginning of the twentieth century, American experiments had already been carried out with underwater electric light powered by generators in the boat.

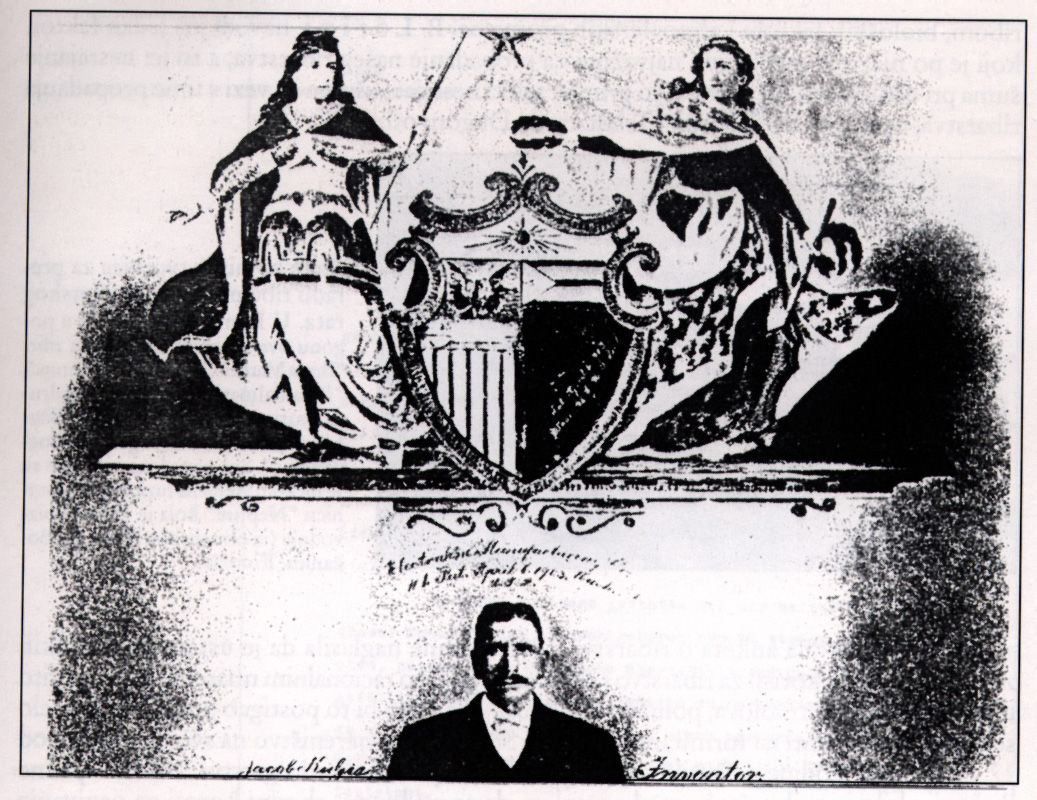

This situation suited Jakov Kuljiš, and in 1903 he managed to patent his invention in the USA, that is, an acetylene lamp for night fishing. For this, he gained the recognition of government officials and was declared an honorary citizen of the United States of America.

Ante Viličić in the fishing kingdom of San Pedro

In his book on the development of tuna fishing, Ante Viličić from Bol on the island of Brač, describes the experience of his first meeting with the world of fishing in the port of San Pedro in California. He says: ‘I was unbelievably surprised when I saw the local modern fishing boats of all sizes and especially the big tuna fishing boats and, on them the special big nets for tuna fishing (purse seines). As I watched them, greatly impressed, I noticed their crew who happily went about their tasks and spoke Croatian, so I felt like I was in some fishing town in my own country.

Viličić mentions the big purse seines which he saw on the stern of the tuna fishing boats. At that moment, three years had passed since Petar Dragić from Crikvenica had constructed a special tuna fishing net – a large purse seine with metal rings at the bottom of the net through which a thick rope was inserted to tighten the net from below so as to prevent the escape of the caught fish towards the sea bed.

Dragić’s tuna fishing net invention – the Revolution in world tuna fishing

Since the beginning of time, fishermen have enveloped schools of fish and hauled the nets to shore. Beach seines have been basic fishing tools since time immemorial. That method of fishing has not changed since ancient times. Fishing was tied to the coast and depended on the configurations of the sea bed. The sea bed had to be smooth and sandy so that the net would not get stuck during hauling to the shore. In ancient drawings of fishing, one can see the exact same way of fishing with beach seines as it was in the Adriatic up to the middle of the twentieth century. Similarly, ancient times knew of high watchtowers for tuna fishing, exactly the same as the ones found today on the Croatian coast in the Kvarner area.

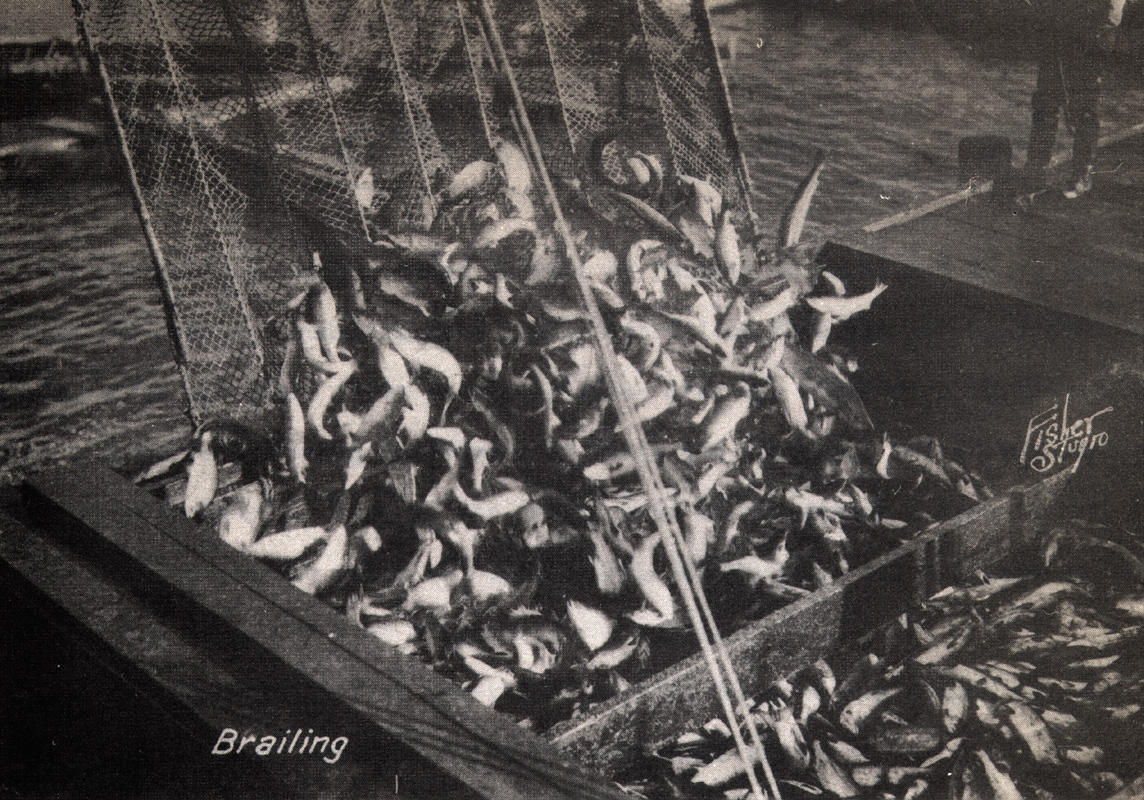

Already at the beginning of the twentieth century, the first experiments were being carried out with purse seines. Only one person had achieved success in this field, the afore-mentioned Ivan Skomerža from Crikvenica. His fellow citizen, Petar Dragić, perfected the concept of the purse seine – the net that does not depend on the shore or on the configurations of the sea bed. He was a fisherman from San Diego, and the money he had saved from fishing he invested in another net – a purse seine for catching tuna. He believed that tuna could be caught further from the shore, so in 1917 near San Diego, he organized the first experiment with his net. Dragić’s net, like others at that time, was made of cotton and covered in tar. That kind of net could not be large because it gave too much resistance in the sea. Dragić’s purse seine was 520 meters long and 57 meters high.

This first attempt with the net was successful. Petar Dragić caught the first tuna with this net in the open sea. That event marked the opening of the oceans’ doors. With this event the huge fishing wealth in world seas and oceans became accessible.

Dragić’s net quickly caught on with the rest of the world and became known, on all seas and oceans, as the Californian type of tuna fishing net. In 1929 in the Adriatic, Ante Viličić from Bol with his recently built tuna fishing boat Napredak, equipped with the Californian type of tuna fishing net, caught the first tuna on the mouth of the Neretva river. It was the beginning of modern tuna fishing in the Adriatic and the whole Mediterranean.

Dragić’s invention caused a real revolution in world fishing. Big tuna fishing boats, which could enter the open sea, were constructed.

The sizes of both nets and boats increased. Factories were constructed for fish processing. At exactly the same time, while Petar Dragić was promoting his new ways of fishing, Martin Bogdanović from Komiza was investing his savings from fishing to construct a fish cannery on Terminal Island in San Pedro.

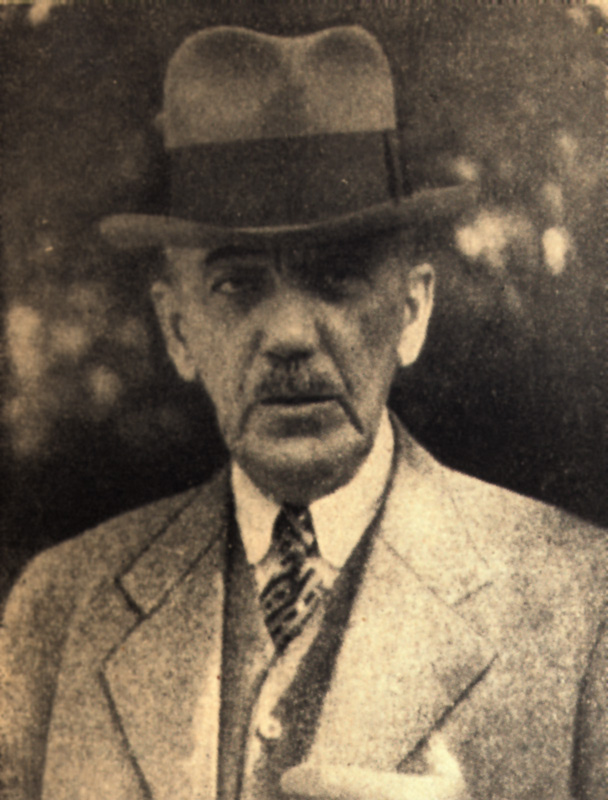

Martin Bogdanović’s fishing industry empire in california

It was the year of 1882 when on the small isle of Biševo near Komiza Martin Bogdanović was born. He lived like all islanders from backbreaking toil in vineyards and fishing. It was the time when Komizian boats braved the waves by oar and sail to faraway islands in the search of sardines.

The story of this important man from Komiza, which was passed down by word of mouth, tells of how, one day, Martin was digging his vineyard and so broke his hoe. He was in a dilemma whether to fix it or to go to America. He decided to abandon his hoe for America. He had just finished his naval service in the Austro-Hungarian Navy and was free to leave his homeland.

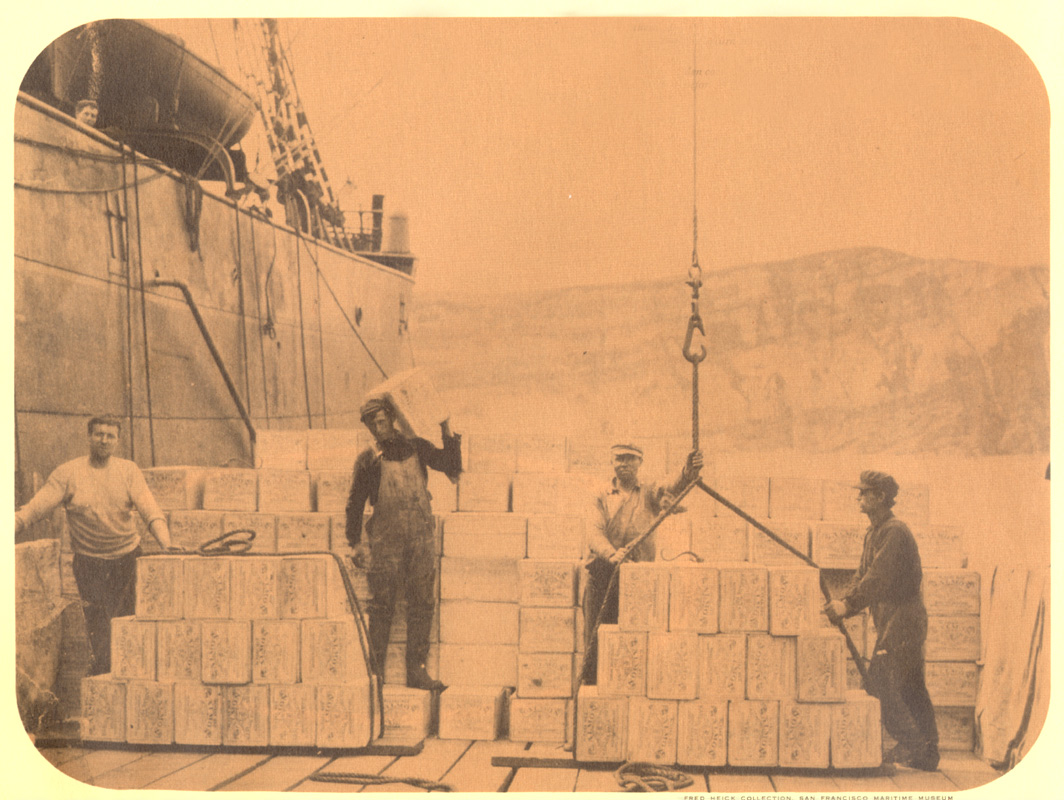

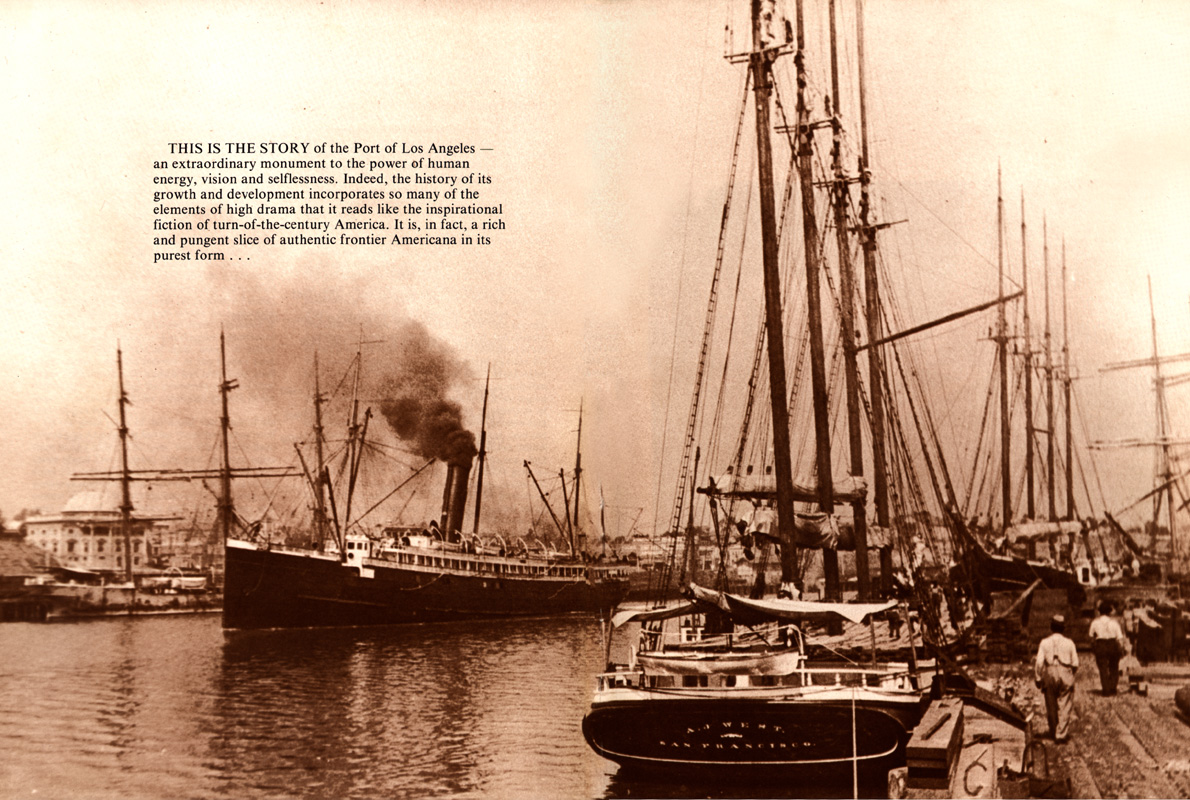

In San Diego he became a fisherman. In 1914, with his savings, he bought a fresh fish trading company which was fire damaged, called California Fish Co. When he increased his income from fish trading, he decided, in 1917, to open his own factory. That year, together with Jakov Mirković and Nikola Viličić, on Terminal Island in San Pedro with US $ 10000 they constructed a fish cannery French Sardine Co, on a surface area of only 600 square meters. It was a time when the doors to deep sea fishing were opening thanks to Dragić’s tuna fishing net. But to enable deep sea fishing, far away from the shore, it was necessary to preserve the fish on the boat. In the book entitled The Port of Los Angeles it is stated that Martin Bogdanović was considered to be the innovator who first used crushed ice to preserve fish. That innovation coincided with the discovery of the purse seine which enabled off shore fishing.

This factory sprouted quickly in the years during the Second World War when tinned food was in growing demand. In 1944, Martin Bogdanović suddenly died and his son took over the running of the fish cannery Star Kist Foods. In 1952 Bogdanović’s cannery expanded into the most modern thunnidae processing operation with a surface area of 13000 square metres on Terminal Island. Its development speeded up rapidly.

This mighty company opened canneries in Puerto Rico, Peru, on the island of Samoa in the Pacific, and opened up operations in Ghana, Japan, New Guinea, Australia, New Zealand and Panama. In 1973, as A. Viličić writes[7], this company produced 120000 tons of fish which was approximately the total amount that the Croatian fishing fleet caught in five years. Thus began Bogdanović’s fishing processing enterprise which was unequalled in the world.

Komiza in the pacific

The author of the book Hrvati i more (Croatians and the Sea), Šime Županović, writes the following about Bogdanović: ‘Bit by bit he took over the whole of the American fishing industry. On Terminal Island in San Pedro in California, he built the biggest fish cannery in America and the whole world. In that factory there worked more fishermen from Vis and Komiza than there are inhabitants on Vis today.

The strength of his cannery was based on the exceptional capabilities and experiences of the people from his homeland to whom the doors of Star Kist were always open. ‘Bogdanović’s cannery for us from Komiza was like our mother,’ says a Komizian fisherman from San Pedro, Vjeko Giaconi, remembering the beginning of his expatriate life in San Pedro. There was barely a Komizian who had not begun his life in America by working in Bogdanović’s cannery. That is the main reason why today in San Pedro there are many more people from Komiza than in Komiza itself.

Martin Bogdanović not only took from his homeland into the world his special art of fishing gained on the waves in the archipelago of Vis, but also the incredible determination, stamina and courage of the off shore fishermen from his homeland, from the times when fishing boats were powered by wind and human muscles.

Martin Bogdanović came from a poor country into a land which offered opportunity to the competent and the courageous, and so, the poor fisherman from the island of Biševo became the greatest name in American fishing history.

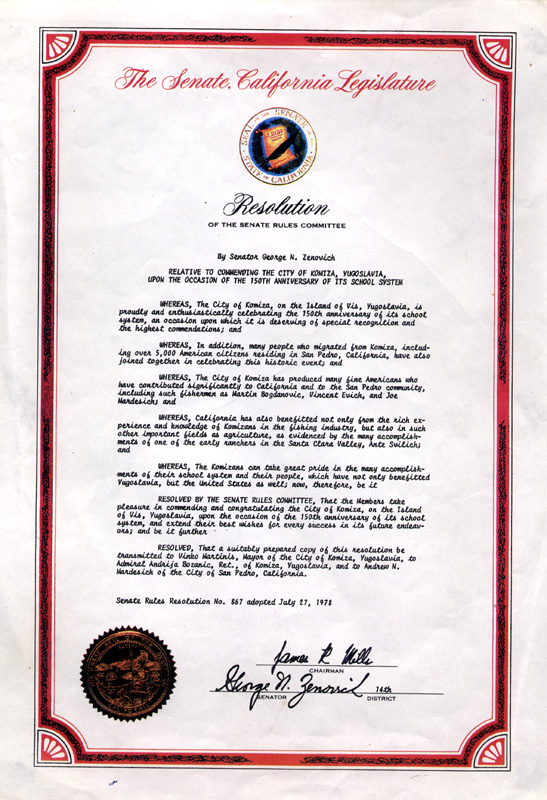

The Californian Senate’s resolution

Californian senator in Sacramento, George N. Zenovich, passed Resolution No. 867 on the twenty-seventh of July in 1978. This was sent to the town of Komiza on the 150th anniversary of its primary school in Komiza. Among other things in the Resolution, it was mentioned that ‘the city of Komiza has produced many fine Americans who have contributed significantly to California and to the San Pedro community, including such fishermen as Martin Bogdanovic, Vincent Evich and Joe Mardesich.

In other words, one small school on a small island in a small country gained a recognition from the Californian Senate because it produced people who contributed to the development of the richest country in the world.

Big Bez from the island of brač on the path to the promised land

Nikola Bezmalinović (Nick Bez) was born in Selce on the island of Brač in 1895. As a young man he dedicated himself to fishing. But the story of the promised land from the other side of the world tempted his enterprising soul and he set off into the wide world. Penniless and not knowing anyone in a foreign land, this well-built young man from Brač disembarked one day in 1910 from a steamboat in New York determined to succeed. His only capital was his exceptional physical strength, his fishing experience gained in his early youth and his enormous desire to succeed. He went immediately to the West Coast because he knew that there were many Dalmatians who were fishermen.

In America, he began his life journey as a fisherman. He needed only six years of fishing to become the owner of a huge salmon fishing boat using purse seines.

As the owner of this new fishing tool – purse seine, he decided to fish in the plentiful waters of Alaska. At that time, purse seine was a novelty. In Alaska, as in the Adriatic, people fished with beach seines. These nets were hauled by horses and much strength was needed for this kind of fishing which was also limited by the configurations on the ocean bed and by the distance from the shore. When the purse seine appeared, the owners of beach seines complained, because this new, more efficient fishing tool threatened their existence. An open conflict emerged between purse seiners and beach seiners. Nick Bez organized the purse seiners and led the clash with the beach seiners. There was a fierce conflict in the battle for existence and affirmation of the new fishing tool which would soon revolutionize fishing. In this clash, Bez emerged as the winner and his victory began a new period in fishing history when fishing became independent of the shore and, for the first time, the wealth of the open sea became accessible to the fishing nets.

In 1945 American president Harry Truman boarded Nick Bez’s boat to go salmon fishing. This was in the Pudget Sound strait near Seattle. This enterprising and likeable man from Brač left such an impression on the President that they became good friends. On that occasion, the President was photographed while rowing together with Nikola Bezmalinović. This photograph which immediately appeared in the media increased Nikola’s popularity, and his friendship with Truman was a stepping stone to enter politics. As a member of the National Democratic Club and the Ministry of Trade, he protected the fishermen’s interests. An anecdote tells of how he used to come to Ministry meetings in fisherman’s clothes when he wanted to protest against laws detrimental to fishermen’s interests. As a result, they called him ‘Dirty Bez’. However, fishermen referred to him fondly as ‘Big Bez’.

Big bez – the pioneer of floating fish factories

Big Bez quickly became rich and created a big fishing fleet. As a fishing magnate he began to invest money in other things. In 1931 he became the owner of the aviation company Alaska Southern Airways.

Another plan occupied Nikola Bezmalinović. He wanted to cut costs by processing fish on board. Experiments with fish processing on board were proven successful and he began his big project in 1931 – which was the creation of the first boat factory. This was a new idea which gained the support of the American government who wanted to achieve world supremacy in the fishing industry. Nick received a cargo ship from the government and adapted it into a factory for fish processing. The reason for this help was that America wanted to be superior to the Japanese who, prior to World War Two, caught and processed 66% of the world’s fishing catch on boat factories. A. S. Eterovich says that the experiment achieved success and was completed in 1948. Then Bezmalinović began to intensively catch fish with his boats adapted for fish processing.

This exceptionally enterprising fisherman from the island of Brač became one of the most influential and richest Croatian expatriates in America. According to Eterovich, Bezmalinović possessed many fishing boats, four big factories for salmon processing, two gold mines and an aviation company.

Twenty-five-year old Nikola Bezmalinović from Brač never imagined in his wildest dreams that he would be so successful when he disembarked penniless from a steamboat in the port of New York in 1910. Big Bez achieved the American dream.

Dalmatians build the biggest floating factory in the world for fish processing

Sardine fishing on the West Coast of America was also developed by Croatian expatriates from Dalmatia. Their specific experience in the fishing, canning and processing of small pelagic fish was greater than in any other kind of fishing. In the USA, they explored the unbelievably bountiful fishing waters.

The most important points for sardine fishing were in San Diego, San Pedro, San Francisco, Monterey and the islands around Vancouver. People fished very close to the coast. In San Pedro, boats with beach seines and later with purse seines caught huge amounts of sardines near the coast. That abundance of sardines made a solid livelihood possible for many fishermen from Dalmatia, very soon after their arrival in America. The area of San Francisco was especially rich with sardines. In shallow ocean waters, near the San Franciscan coast, huge amounts of sardines were caught so that at times the market was flooded with fish.

Adam S. Eterovich in his book Croatians in California 1849-1999 describes an especially enterprising group of Dalmatians. Eterovich names the following: M. Botica, J. Botica, N. Mezin, S. Gargas, A. Zitco, C. Gaspar, P. Dragić, N. Dragić, N. Perich, F. Mezin and V. Giaconni. These fishermen were the owners of all together ten sardine fishing boats.

They all caught sardines on fishing posts in the waters of San Francisco. At that time, the market for canned fish was saturated. People had not developed a taste for canned fish. The market for canned fish had not yet been created, so supply was greater than demand.

The situation for fishermen who caught sardines, as Eterovich writes, worsened considerably when Californian law radically limited sardine fishing for canning. That law threatened the fishermen greatly and they were confronted with ruin.

Describing the enterprise which this group of fishermen had undertaken, Eterovich writes: ‘Here is where the native ability and resourcefulness of these fishermen came to the surface. They pooled their resources, mortgaged every bit of property that they owned, and together with Americans J. Bersten and J. Lockhead and Capt. Hansen of the Lansing, an 8000 ton freighter, formed the Fishermen Produce Company, Inc. They purchased the Lansing and turned her into a reduction plant (the value of the Lansing and the equipment was close to $ 200,000) for the purpose of reducing sardines to oil and meal. They anchored the Lansing three miles off the coast of California in order to evade the operation of the Californian law, had their trawlers feed sardines to the Lansing and reduce sardines to oil and meal.

Thus, that group of enterprising Dalmatians, in a moment of crisis which threatened their livelihood, found a way out and affirmed a new model of production on the open sea in America. The law could not deter them in their work because the boat was located in waters out of the jurisdiction of the Californian government. The law did not prohibit the produced goods from being brought to shore, so they were legally able to transport products from their floating factory three miles away from the coast to the Californian market.

As can be seen from Eterovich’s list of fishermen, Petar Dragić, the inventor of the tuna fishing net participated in this pioneering enterprise together with his brother Nikola Dragić.

‘Today’, Eterovich states, ‘these fishermen proudly assert that the Lansing was the biggest floating factory in the world.

Mario Puratić from the island of brač changes world fishing history

Mario Puratić left his birth island of Brač in 1938. He was a fisherman on many tuna fishing boats which fished in the Pacific. People who knew him as a fisherman say that he always dreamed of making the fishing procedures more efficient.

The invention of the tuna fishing net in 1917 opened the door to deep sea fishing. Big tuna fishing boats were built and as a result, bigger nets were needed. The first purse seine for tuna fishing, promoted by Petar Dragić in 1917, was only 570 meters long and 57 meters high. With a net of this size, deep sea fishing was inefficient. It was essential not only to build bigger ships but to make larger nets as well. But size was limited by the material, in this case cotton, from which the nets were made and by the number of crew members able to haul out the net and its catch onto the deck. Increasing the size of the net meant increasing the size of the crew. Nets were made of thick cotton thread covered in tar for added strength. Such a net gave resistance in the water especially in strong sea currents. Consequently, the biggest problem was the physical strength needed for the manual hauling of the net onto the deck. The increase of crew members meant lower economic return. Also the cotton net often broke with large catches.

This situation was the challenge Mario Puratić dreamt of. To try to lessen the struggle of the fishermen in hauling the nets, he decided to construct a spinning device which would lift the net from the sea and spare the fishermen’s strength.

The invention which changed fishing history in the twentieth century

Puratić’s prototype was completed in 1944. This still was not the hydraulic device which we know of on today’s fishing boats, but a pulley which spun with a help of a rope.

He tried to find help for research. Tone Mihovilović, a Komizian fisherman from San Pedro, told me about his friend Mario Puratić. He remembered the moment when Puratić came to him to ask him for advice about his invention. The story goes: ‘Mario says to me: I’m broke, how can I patent this? And I say to him: Are you sure this will work? Of course he was sure. He trusted me. He asked our Association San Pedro to help him but they didn’t. So he went to Seattle.’

Another Komizian fisherman from San Pedro, Pjerin Bucci, who from 1954 to this day catches tuna in the Pacific, talks of how Mario Puratić was his crew member for years. He says the following about his invention: ‘The revolution in fishing began when cotton nets were exchanged for nylon ones and when we started to fish with power block. It wasn’t easy for Mario to patent his invention. He first offered his power block to ‘Star Kist’ but they weren’t interested. He then offered it to Anton Mišetić who was a famous fisherman in San Pedro. Anton Mišetić tried it, but he said it wasn’t appropriate. Then Puratić went to Seattle and offered it to the MARCO company. This was the Marine Construction company or MARCO for short. And there the engineers immediately saw that it was a good thing and wanted to buy the patent from Puratić, but he didn’t want to sell and went for a percentage. Today there isn’t a fishing boat in the world without a power block.’

With the application of Puratić’s invention the crews were halved and the nets gained bigger dimensions. These kinds of nets became more efficient because they could envelop a larger amount of tuna and the whole process became faster. Puratić’s power block was not only confined to tuna fishing but was applied to all kinds of fishing where fishing tools had to be hauled from the sea.

The tuna fishing net which Petar Dragić promoted in 1917 in San Diego was now being perfected. It became larger and larger, but its size demanded a quicker sinking speed. Josip Viličić from Bol on the island of Brač made a contribution with his innovation in 1947. He was the first to exchange lead weights with a steel chain which enabled the net to sink more quickly and tear less often.

Puratić’s invention, which was patented in 1955, coincided with the innovation in fishing which another man from Bol, Mike Pulišelić, instigated in the same year. This man from Brač was the first to use a synthetic material to make his purse seine. The following year, in 1956, the first purse seine made completely of synthetic material and made by Ante Nižetić from Selca, appeared. Only now could Puratić’s invention come to the fore, because the size of the net was no longer limited by the strength of cotton thread. The power block and nylon thread made the huge proportions of modern nets for tuna fishing possible. They could now be up to 1400 meters in length and 140 meters in height.

Canada gave this great man from Brač the special honour of putting his invention on the five dollar note.

Ante Fiamengo – fishing by phosphorescence (ardura)

Fishermen from Komiza after centuries of catching sardines with gill nets (vojga) developed the exceptional art of searching for fish in the dark depths of the night by phosphorescence of the fish itself. That light which the fish radiates while moving in the dark night was called ardura. But only a few rare fishermen knew how to exploit this knowledge and jealously guarded their secret.

Just as Croatian fishermen had taken much exclusive knowledge about fishing into the New World, so did this art help Ante Fiamengo from Komiza to achieve the upper hand in fishing which was unexplainable for a long time.

Ante Viličić writes the following about Ante Fiamengo’s art: ‘One tuna fishing season when the method and possibility of catching fish by night phosphorescence (ardura) was still unknown, a tuna fishing boat whose owner was Ante Fiamengo from Komiza, would for many days catch great amounts of tuna and take them to San Pedro and not one of the tuna fishermen knew how or where. As he fished for tuna at night, it was impossible to ascertain where he was fishing. The other tuna fishermen were enraged that he was catching tuna and that they could not find out where. After many days they managed to trace him. Pursuing him, they discovered that he was fishing by night and not by day. The news of how and where he was fishing quickly spread. (…) However, Ante Fiamengo’s boat, for some time, still caught more than the others.’

Tone Mihovilović Bejota – Galapagos’s purse seiner

The Galapagos region was exceptionally rich with fish. On its fishing posts, fishermen enveloped huge amounts of sardines, horse mackerel, pelamides and tuna. The problem was that the nets were often torn because of the various configurations of the sea bed and oscillations in the depths of the sea.

Komizian fisherman Tone Mihovilović Bejota caught fish for many years in the waters of Galapagos and was confronted with this problem of the net tearing. He decided to construct a special net which could be shortened. Between the highest and the lowest part of the net, at thirty meter intervals, he put ropes which meant that he could determine its height and the way the net would fall during the catch in order to avoid it getting caught on the rocks at the bottom of the sea. With such a net he could envelop the fish ten meters below without fear of tearing the net.

Tone Mihovilović never patented his invention. Being of the old school, he taught others how to construct nets like his. On Galapagos, even today, fishing is carried out with Mihovilović’s kind of purse seine.

John Resich fishman – the inventor of the spray system

In 1990 in San Pedro, I met a fisherman one day with whom I could speak in the Komizian dialect even though he was born in America and had never been to Komiza. His name is John Resich (originating from Reskušić) and his nickname is Fishman.

His parents were from Komiza and had come to America at the turn of the century. His father was a good fisherman thereby gaining the nickname Fishman, as did the whole family (exactly like in ‘the old country’, as John Resich says).

In his youth, he experienced the dangers and hardships of fishing before the technical revolution in fishing. The heart of the problem was unloading the tuna. The fish was frozen in pools on board, and ice had to be broken with axes, picks and chisels, so that the frozen fish could be unloaded.

This problem prompted John Resich, as he told me in 1990 in San Pedro, to begin experiments to ease the problem. He noticed that the sea water had a lower freezing point when a certain amount of salt was added. He realized that the fish could be frozen without forming an ice block which made unloading difficult. In his boat he installed pumps to circulate the salted sea water from the bottom of the pool through the cooling pipes to fall from the ceiling of the pool onto the fish. In this way the constant movement of salted water maintained coolness, the fish was frozen and it was easy to unload it.

John Resich did not even think of patenting his invention. It was only when he saw other boats using his spray system that he realized that he had failed to protect his invention.

It is interesting that in his story John Resich considers himself a true Komizian even though his only ties with Komiza are his parents and the language learned from fishermen: ‘People from Komiza were the best fishermen, second to none. Those who came from Komiza after 1939 aren’t true Komizians. You know, different sort, different schooling. They turned into Americans.’

Therefore, in the fishing world of America, up until the Second World War, the word Komiza was synonymous with exceptionally talented fishermen, and John Resich was happy to identify himself with them. He emphasises the difference from those who came from Komiza when the pioneering phase of American fishing had passed, as technology took over the specific capabilities of the fishermen who were the heirs to a thousand year long tradition of deep sea fishing in the Adriatic.

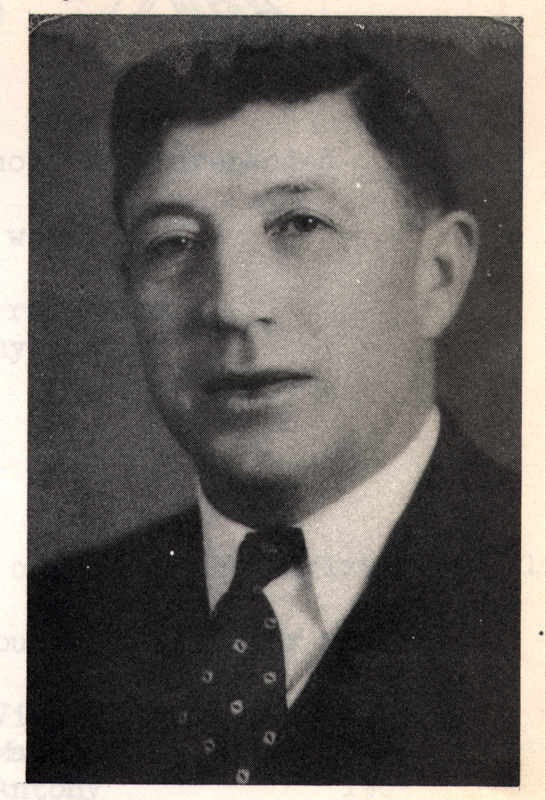

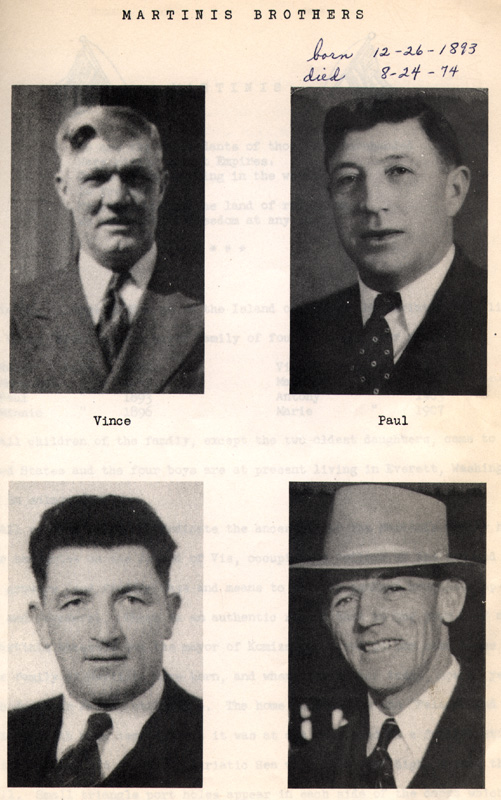

Paul Martinis from Komiza: the salmon king

Paul Martinis was born in Komiza in 1893. Before doing his few years of military service in the Austro-Hungarian army, he decided to go to the USA in 1913. He boarded the steamboat Martha Washington in Trieste and, after an eighteen day journey, disembarked in New York without knowing a word of English and only $ 22 in his pocket, but he had his huge fishing experience gained from fishing with his father in his early youth.

He arrived in Astoria, in Oregon state, and immediately found work in a restaurant stoking the fire. Hearing that there were fishermen from Komiza in Tacoma, he set off in search of fishing work. There he met Nikola Mardešić whom he knew from Komiza and on his boat Sunset earned his first dollars salmon fishing. In Anacortes, in 1916, he bought his first salmon fishing boat Sloga. He caught salmon at the mouth of the river Columbia and in Pudget Sound near Tacoma and Seattle. Already in the following year, after a successful fishing season, he built Northland, a new twenty meter boat. On this boat Pavao Martinis took the role of Captain for the first time and went towards Alaska, to the Bering Sea, in order to spend the salmon fishing season there. This was a risky enterprise for someone who was still unfamiliar with this dangerous sea. His success in fishing paved the way to new fishing endeavours for which he was to become famous in America.

It was a pioneering time of fishing in Alaska, when fishing was still powered by sail and oar. Robert A. Henning, in his book about salmon fishing in Alaska, relates the following about this period: ‘It was a terrible time to remember. It was the time when Ketchikan was the world capital of salmon fishing and fourteen factories worked to full capacity day and night for two or three months every summer…’

This time was best described by John Resich whose roots were from Komiza. I recorded his story in San Pedro in 1990: ‘At that time when we fished in the Bering Sea, we had no engines, only oars. And in the morning when you got up, you had to piss on your hands to get your fingers moving. Because your hands stiffened, your fingers swelled from the cold and the work. I’m not a big man, but I have hands like John Lewis, the boxer. You had to take your boots in your teeth, because you couldn’t hold them with your hands. You couldn’t believe it. Had there been a steamboat, everyone would have escaped. You couldn’t stand it, it was unbelievable, and it wasn’t even winter but summer – May, June, July, August. And we would throw the nets up to twelve times a day. And up there, the day lasted twenty-four hours. We slept three or four hours a day.

Then, at that time in the Bering Sea, only people from Komiza were fishing – the three Martinis brothers and Dinja, Drinda, Zverce, Konjic, Guja, Kroj, Tetus. There were also fishing traps set by the Indians. And the people from Komiza paid the Indians to remove the traps, so that the Komizians could fish with their nets.’

In those harsh fishing conditions, Paul Martinis became the most successful fisherman. He was an expert on sea currents which, in salmon fishing, is of exceptional importance. His fellow fishermen say that he used to watch the swaying of sea weed on the sea bed while his boat was moored in harbour. Accordingly, he would predict changes in sea currents, which gave him the competitive advantage over other fishermen. This skill, together with other useful techniques, has its origin in the old traditions of Dalmatian fishermen. While fishing for sardines, the Komizian fishermen developed very refined and subtle methods for deciphering all kinds of signs essential for navigation and fishing. In new circumstances, these skills represented that differentia specifica which gave our fishermen the upper hand over others.

Pavao Martinis went down in the history of American fishing not only because of the record catches of salmon in Bristol Bay and the Bering Sea, but also as the first American fisherman who discovered salmon in the rich and dangerous waters of the Aleutian Islands. America acknowledged him officially for his fishing endeavours by awarding him the title King of Salmon, given to him by the president of the United States, Eisenhower.

Ante Viličić from Bol – pioneer of Modern meditearanean tuna fishing

Ante Viličić from Bol on the island of Brač, like many other people from Brač and Dalmatia, was hit by the post World War One economic crisis and left his home country in search of a better life. He had a brother in San Pedro and it was upon the latter’s invitation that Viličić left for America in 1920. Viličić says of his first experience in the fishing port of San Pedro: ‘I watched many fishing boats and their catches of fish which the crew tirelessly and speedily unloaded so that they could go out fishing again. Observing this, in my heart, I was, in one way, happy and, in another, it hurt me to think of how we in the old country still fished primitively, with oar powered boats and other antiquated fishing equipment, in the same way people fished 500 years ago. Within me the desire and thought that the same changes could take place on our waters was born. This same drive remained a part of me the whole time I was there.

On the tuna fishing boat Suprim, Ante Viličić gained experience and knowledge and passed the best possible school for tuna fishing in the world’s fishing metropolis, San Pedro. But Ante Viličić took all this in with the thought of how he could put it into practice in his own homeland.

Having saved some money, he decided in 1928 to return to his home island of Brač. In Sumartin, he had the Brač returnee from America and boat builder Šime Kasolini construct a modern tuna fishing boat.

The boat was built in five months in Sumartin’s shipyard in 1928. It was approximately 17 meters long and had a 75 HP engine built in. When Viličić gained the opportunity in America to compare the fishing situation in Dalmatia with the one in San Pedro, he came upon the idea to help his home town improve its outdated fishing techniques. The name Napredak (Improvement) with which he christened his boat, expressed that idea. This boat was the first modern engine powered tuna fishing boat on the Adriatic and in the Mediterranean, and set sail for the first time in early October 1928.

On the sixth of June 1929, Napredak set sail from the port of Split on its first fishing trip. That day marked the beginning of a new era in tuna fishing on the Adriatic and Mediterranean with the first engine powered tuna fishing boat and Californian type purse seine.

Based on Viličić’s purse seine, Ante Domančić from Hvar went on to make the first modern purse seine for summer fishing of small pelagic fish. Domančić’s purse seine with kanistrele (metal rings at the bottom of the net) was the first of its kind in the Croatian Adriatic.

It must be known that, at that time, in the whole Mediterranean there were only two ways of catching tuna: by trolling lines or with gill nets for tuna (Italian: tonnara). This method for catching tuna existed from ancient times and had not changed greatly till the 1950s.

In 1937, in the Adriatic there were only six engine powered tuna fishing boats. Apart from Napredak from Bol, there were three from Kali on the island of Ugljan: Vitlov, Tunolovac and Kolega as well as Sveti Ivan from Crikvenica. The first Italian engine powered tuna fishing boat did not appear until 1950. In Italy in the 1950s, the tonnara method still dominated. In Greece oar boats were still in use, while in France and Spain trolling lines for tuna fishing were mainly used. This is the background we need to be aware of, in assessing the importance of Viličić’s enterprise when he decided to apply his experience gained in America to his own homeland.

Mateo Zlatar from Brač: pioneer of the Chilean fishing industry

It is difficult to determine the role of Croatian fishermen in the fishing industry of Chile. It is an area still unknown to us. It is certain that our expatriates in South America who were present in large numbers from the 1870s, made a considerable contribution at various levels of economic, social and cultural life. However, no one as yet has seriously researched the fishing history of this continent and the part played by Croatians in this history. Before undertaking such research, we must be aware that only the oral tradition exists, which was recorded in Komiza during conversations with returnees from Chile.

The story goes that, due to phylloxera (vine disease) destroying the vineyards after World War One and the barren sea, two people from Vis joined the wave of migration which pushed Dalmatians into the wide world. They were Jure Zorotović Lovin from the village of Okjucina and Ivo Vidović Sibetov from Komiza.

They came to Chile without knowing anyone, penniless and unemployed. And so they wandered along the coast of Antofagasta always staying near the water, hoping that someone would offer them fishing work. They went on for long without money and food, tired, hungry and thirsty. They could get a job in the saltpetre mines, but they knew that they would have little chance of escaping from that laborious and poorly paid work. They hoped that someone would offer them fishing work because that was the only kind of work they knew.

One day, they saw in a cove barefooted people with their trouser bottoms turned up, paddling in the water. As they came closer, they saw the crowd of men and women grab something from the sea with baskets and aprons. The whole cove was filled with sardines and anchovies. Men and women carried baskets and aprons laden with fish. Ivo Vidović from Komiza was wearing a straw hat. He realized that the two of them had the opportunity for a feed after such a long time, so he turned up his trousers and went fishing with his hat.

Vidović filled his hat with sardines and anchovies. They found dry branches on the coast, lit a fire, cooked the fish and had a good feed. They came back the next day and saw that the tide was out and, in the holes on the sand, fish had been left behind. Once again they saw people picking up the fish and carrying it to the shore. Again they took some fish and cooked it. Happy to be able to feed themselves independently in a foreign land, their conversation turned to trying to salt the fish and preserve it. They constructed a rough shed made of wooden boards and driftwood and there they salted the anchovies as they had done in their homeland.

After some months, the salted anchovies were smelt by others and buyers became interested and our two fishermen with straw hats earned handsomely.

The story goes that they then met Mateo Zlatar from Povlja on the island of Brač, who worked in the saltpetre industry. Zlatar showed interest in their discovery and began to salt the fish himself. The fish was brought to them by other gatherers and they salted it.

In Komiza the old factory owners would customarily add a certain amount of nitrate when salting fish. This was done when the market demanded the fish to be salted as soon as possible. These two Komizians, during salting added a lot of nitrate, as it was readily available and cheap. This enabled them to sell the salted fish quicker. Mateo Zlatar only salted his fish with sea salt. And, after a certain amount of time, when they expected the fish to mature, these two Komizians realized they had made a mistake by adding too much nitrate. All the fish was ruined because the nitrate had eaten it to the bone. On the other hand, Zlatar from Brač made a profit which enabled him to become the pioneer of the fishing industry in Chile. The two men from Komiza left Antofagasta and, in Santiago, opened a grocery store while Mateo Zlatar became a fishing industrialist.

Dane Mataić Pavičić in his book Hrvati u Čileu – životopisi (Croatians in Chile – Biographies) says the following about Mateo Zlatar: ‘He came to Punta Arenas in Chile on the thirty-first of January in 1926. He soon settled in Antofagasta. He began to work in trade and the saltpetre industry, and later on he fished (…). He began to can sardines in oil, using technology which was until that time unknown in Chile. Thus, he became a cannery owner and his line of products carried the name Sardine Zlatar. In 1974 he owned five fishing boats, 650 ton capacity store rooms and 200 employees. Yearly production amounted to three million cans of sardines and shellfish in oil, six thousand tons of fish meal and five hundred tons of fish oil.’

Dalmatians lead world fishing expeditions

Dragić from Crikvenica captains the American fishing expedition to China

America in the fifties began several new fishing expeditions to spread Californian style tuna fishing around the world. Within the FAO program of the UN, the post World War Two America sent its first fishing expedition to China so that American fishermen could help their Chinese counterparts to learn the art of modern fishing.

On that occasion, the USA gave China several fully equipped modern tuna fishing boats and sent them off together with the best fishing crews who would teach the Chinese to master contemporary fishing technology.

The crews were made up mainly of fishermen from San Pedro who were of Dalmatian origin. A. Viličić writes in his book Tuna Fishing on the Adriatic that this expedition was led by Nikola Dragić from Crikvenica, the brother of Petar Dragić who achieved fame when he constructed modern nets for tuna fishing in 1917.

Tuna fishing in Australian waters

The second American fishing expedition undertaken with the aim of teaching fishing using Californian style nets, was in Australia. The leader of that fleet was Californian fisherman Kuštre, who originated from around Šibenik. At that time, tuna fishing in Australia was not yet developed. There was only game fishing using trolling lines or fishing rods.

Viličić writes that, even in Australia, the pioneer of fishing with Californian type nets was a Croat – Ante Lukin from Kali on the island of Ugljan. In 1974 he promoted the most efficient kind of tuna fishing in Australian waters.

In Australia, tuna fishing was dominated by bamboo rods and live bait and the fishermen from Kali were superior in that field.

The world’s recognition of dalmatian fishermen from california

The revolutionary changes which occurred in the twentieth century were mainly the impetus of our uneducated fishermen. They were people whose arrival in America gave them the chance to apply their fishing knowledge in new conditions of deep sea fishing. These conditions offered new possibilities for catching enormous quantities of fish. Determination, stamina, intelligence and their desire for success produced a world phenomenon: uneducated people with limited knowledge of English and no formal qualification became world educators and researchers in the expeditions undertaken by the mightiest country in the world.

Apart from the afore-mentioned expeditions to China and Australia, the research expedition in the Atlantic must be mentioned. A. Viličić writes of the latter: ‘Our fishermen at the beginning of 1951 were sent by the USA to find out whether there was tuna in the Atlantic and whether they could organize fishing on the regular basis there. From San Pedro they sent Šime Branko, originally from around Šibenik, as the leader, and Vido Drušković from Korčula, as a scout, together with other fishermen from San Pedro. They discovered schools of tuna which they fished successfully.

Something interesting happened in 1947 when Komizian Mate Martinis from Everett in Washington State brought a modern American boat to Komiza. This was a present to Komizian fishermen which was a part of post-war humanitarian aid from the UNRA. That present was rejected by the elderly Komizians who were afraid that the new American contraption would threaten their century long fishing tradition. Meanwhile, the younger ones who had freed themselves from the constraints of the old school were revolutionizing world fishing with their innovative inventions. However, the secret of their fishing success lay exactly in the experience that they had inherited from those old people belonging to the old school representing centuries spent on the sea. But, for that experience to yield world results, it was necessary to have a social context which offered new freedom and encouraged those young people to become enterprising in the face of the enormous untapped fishing wealth of the oceans.

Ante Dundov Kongo from Kali in Žuanić’s fishing empire

Confessions from the king of the ocean

It is difficult to say where the well-known fisherman from Kali on the island of Ugljan lived the longest. In which country, in which town, in which street? He actually spent most of his life on the sea, sailing the oceans or flying by helicopter over the endless Pacific in the search of fish.

I listened to his story:

‘I was a fisherman in Peru, Equador, Galapagos, Africa, the whole Californian coast and then on the Neptune Bank in Venezuela. And I brought young people from Kali to fish with me. We fished where the dolphins were. Where there are dolphins, there is tuna.

I think that in my life I have caught around 154 thousand tons of tuna and pelamides and an equal amount of anchovies. In my life I have caught more than three hundred thousand tons of fish. Which is more than our fishermen in the Adriatic catch in ten years. I don’t know of anyone in the world who has caught more fish than me. I fished on the boat Apollo which got its name when the first men went to the Moon. It was the biggest tuna fishing boat in the world. In one trip, we once caught 2240 tons of tuna. That was a record. No other boat has brought more fish.

In my life I have lived more on board a boat than at home. My wife bought a nice new carpet for the living room and I said to her: What use is a new carpet when there’s no one to walk on it? I’m never home. Always at sea. I would never recommend my job to anyone, not even to my worst enemy. Once I fell from a height of 7000 feet from a helicopter into the ocean. I was a four hour boat ride away from my own boat. My pilot was killed. I swam around in the middle of the Pacific while holding this dead Peruvian to stop him from being swept away. I held him dead for three hours and I swam. When they found me I was still floating senselessly.

I had many opportunities to help my family in Kali. Komizian Joe Bogdanović, the owner of the Star Kist cannery in San Pedro, trusted me and I could bring whoever I liked on board. And I invited my people from Kali, I wanted to help them, I could guarantee for all of them.

But, my late mother said to me: ‘My dear son, there will be no one left to bury me! You’re taking people from Kali to America and Kali is becoming deserted. Who is going to bury the old people when they die?’ And that hurt me, by God, that hurt me! And so I started to bring over the people from Kali on the condition that they return home and that they invest their money in their own houses and properties. That’s how I helped them. I said to them: ‘Now, you go on board for three months and then go home, and invest your money in your own property.’ Today Kali is a rich place. Everyone has built a new house.

And what that Japanese man in Osaka said when I told him that I was from a small place called Kali with 700 inhabitants: ‘How is that possible’, wondered the Japanese man, ‘there are 700 of you but wherever you see a boat sailing on the ocean there is a man from Kali on board. I thought that there must be a few million of you!’ So spoke the Japanese fisherman from Osaka. Our people from Kali have become known throughout the world as the best fishermen. Before, Komizians were the best, but today people from Kali are.

The best fishermen in the world were Komizians. No one rivalled them until the sixties. They fished from Alaska right down to Cape Horn in Chile. People from Brač were also well known. Trutanić from Brač was a great fisherman in San Pedro. Dirty Bez from Brač earned a fortune from fishing.

Bogdanović’s cannery enterprise expanded from San Pedro to Puerto Rico. Komizian Joe Bogdanović built a cannery there, investing a lot of money. He sent Komizian women from the San Pedro cannery to teach women in Puerto Rico how to clean fish. Komizian women were even sent to his cannery on Samoa in the Pacific for the same purpose. This work was tax free, because it was part of America’s aid to help those countries develop their fish industry.

Everything that was invented in the world of fishing in the last hundred years was invented by Dalmatians. Norwegians were famous for using lines and hooks. The Polish became famous when the trawlers began. The Portuguese are the best in navigation. And we are the best net fishermen. No one has the work stamina of Dalmatians. Wherever you go in the world, everyone knows about Mario Puratić from Sumartin on Brač. Today every fishing boat has the power block that Mario invented. From Japan to Chile, from Alaska to Cape Horn, wherever you go in the world, all fishermen know about Puratić. Only Croatia doesn’t know about Puratić. Croatia doesn’t know what it has given to world fishing in the last hundred years.’

Žuanić’s fishing empire on the pacific

That is the story of the fisherman who originated from the small fishing willage of Kali on the island of Ugljan and who is probably the world record holder in fishing. He is the man who deserves the most credit for making Kali famous today in the fishing world and on all oceans. He is also the man whose dream was to restore life to his birthplace through fishing on the Pacific.

Ante Dundov Kongo was the fisherman who was responsible for the development of the fishing giant which was established in the 1980s by Lawrence Zuanich. In Eterovich’s book Croatians in California, amongst the biographies of well known Californian Croats, the biography of Lawrence’s father John Zuanich born in Komiza in 1985 can be found. John Zuanich came from Komiza to Bellingham (Washington) in 1913. In San Pedro, he began to form his own fishing fleet which his son Lawrence Zuanich was to develop under the auspices of his mighty fishing corporation Zi Company.

In the eighties, Lawrence Zuanich had thirteen of the most modern, fully equipped tuna fishing boats on the Pacific and was catching around a hundred thousand tons of tuna a year. At the beginning of the eighties, in all the world’s seas, around 3500000 tons of fish were caught, which meant that Zuanich’s fishing fleet alone caught the thirty-fifth part of the world’s catch of thunnidae. This fisherman, originally from Komiza, in the eighties created a fishing fleet of unequalled efficiency in world fishing history. The best fisherman on Zuanich’s boats, Ante Dundov Kongo, together with the crews made up of his people from Kali, can take most of the credit for creating Zuanich’s fishing empire on the Pacific.